CONTEXT

Material research has been an important focal point in product design for decades. While there is significant work on understanding how materials shape our experiences, most of this research is described from a predominantly human-centred perspective. Efforts are made within the field of design to stray away from human-centred design and toward more porous, ecological, and relational understandings of tools, materials, and design practices. However, there remains a gap between post-human theories and design practices. To bridge the gap between sustainable debates and material-driven design practices, this project illuminates the possibilities of using more-than-human theory in designing new materials.

The Project

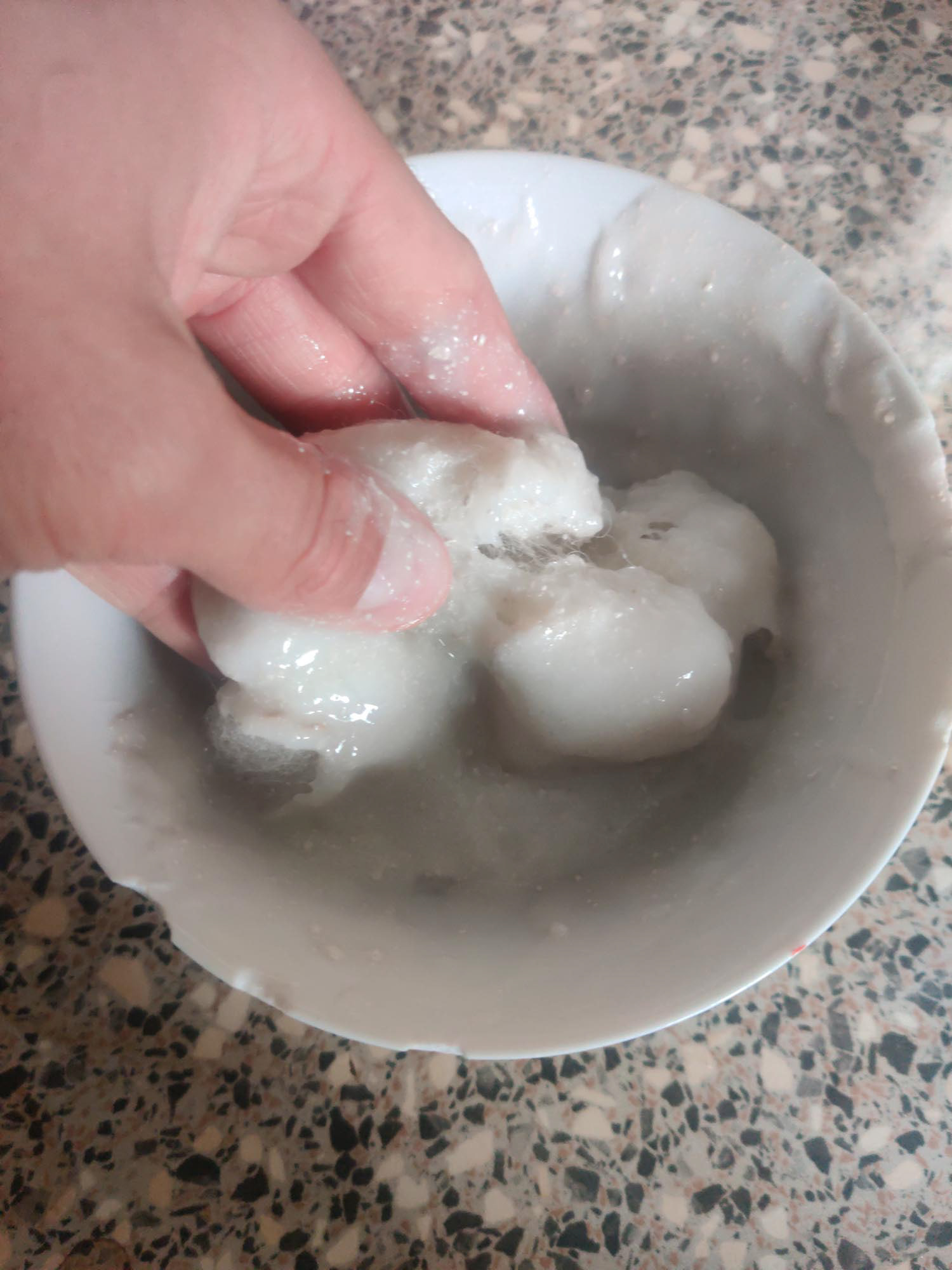

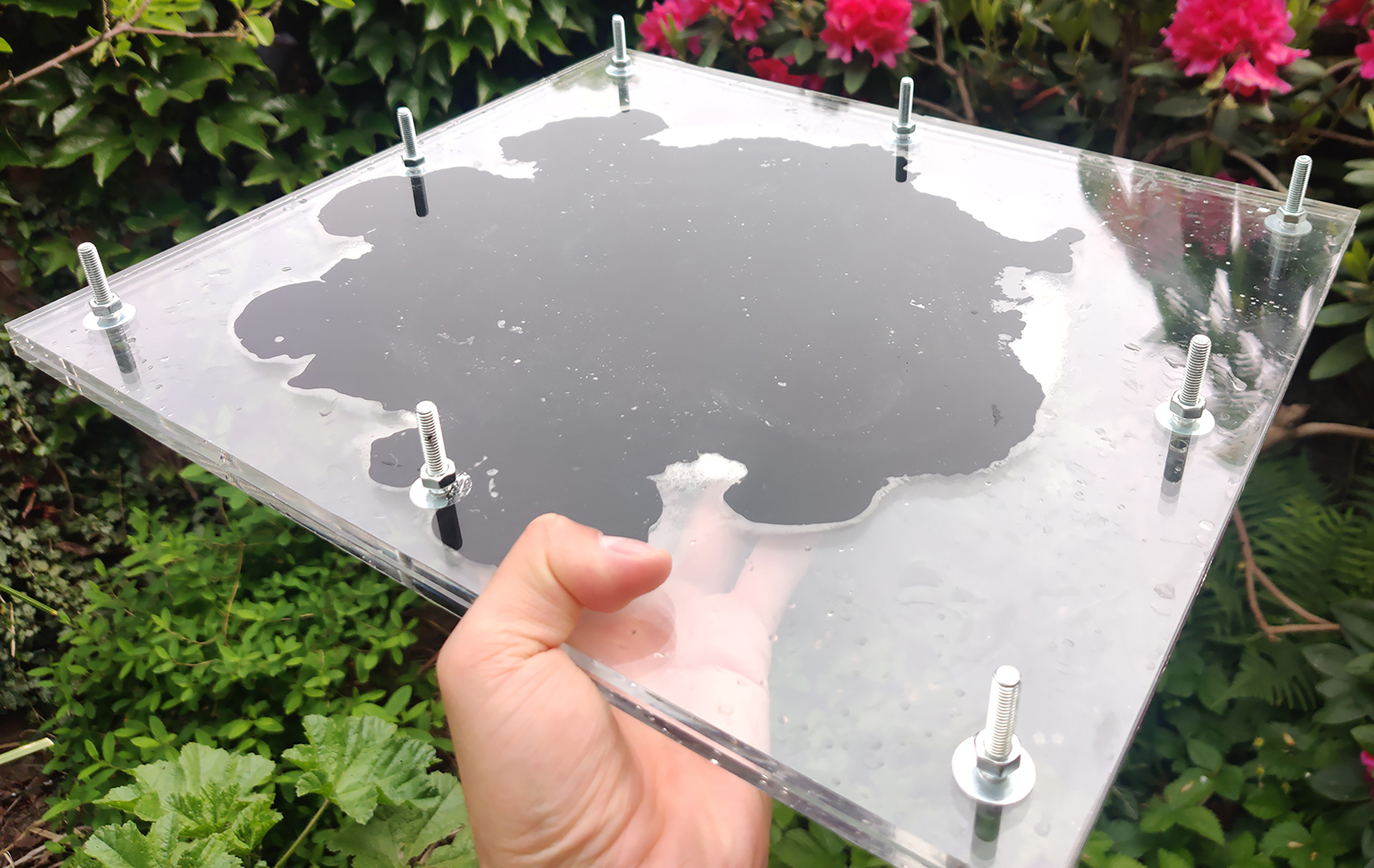

In search of new and valuable compound materials with Dutch wool, composite materials with Dutch wool and simple-to-make bioplastics were created. During this process, specific actions were taken to allow non-human participation. For example, to understand the relationship between the wool and its landscape of origin, a landscape ethnography study was performed. This study led to the inclusion of several non-humans like nettles and cow parsley fibres. Moreover, while creating the materials, attention was paid to the fragile and precarious moments. Instead of basing it on personal biases, the material was left to speak for itself. Eventually, this resulted in a novel technique to make strong and flexible sheets with wool and bio-composites. The sheets can endure a lot of tensile force and can be made at home using easy-to-make bio-composites. Moreover, the wool does not need to be felted, woven, or knitted, and can be used immediately after it has been cleaned.

Landscape Ethnography

The project employed two methods to allow non-human participation in the design process. The first approach involved conducting a landscape ethnography study. Rather than treating wool as a generic material and universalizing the landscape of origin, the project emphasized the unique and distinctive qualities of the landscape from which the wool originated; the dikes along the Maas between Lith and Ravestijn. The primary objective of the landscape ethnography study was to gain insight into the intricate relationship between the sheep and their specific environment. This in-depth understanding sheds light on the relationships that should be included in the design process and how design decisions could impact these relationships.

The project employed two methods to allow non-human participation in the design process. The first approach involved conducting a landscape ethnography study. Rather than treating wool as a generic material and universalizing the landscape of origin, the project emphasized the unique and distinctive qualities of the landscape from which the wool originated; the dikes along the Maas between Lith and Ravestijn. The primary objective of the landscape ethnography study was to gain insight into the intricate relationship between the sheep and their specific environment. This in-depth understanding sheds light on the relationships that should be included in the design process and how design decisions could impact these relationships.

within the sheep enclosures, stinging nettles become visible and prominent as the grass around the stinging nettles is eaten away by the sheep. The sheep do not dare to touch the nettles and cleanly eat the vegetation around the stinging nettles. Sometimes, large bushes of nettles form. This can repress other plant species and weaken the dike's structure. This begs the question, is it okay for me, as a designer, to cut the nettles and use it as a material source? Is this the right moment to interfere?

FIELDNOTES

Without the sheep, the nettles will prevail? They will repress other plants? And, creates bald spots on the dikes in winter? The sheep keep them at bay. Yet, sometimes the nettles will get away. Is this when we intervene? Can we use this now? Is that what the sheep mean?

Without the sheep, the nettles will prevail? They will repress other plants? And, creates bald spots on the dikes in winter? The sheep keep them at bay. Yet, sometimes the nettles will get away. Is this when we intervene? Can we use this now? Is that what the sheep mean?

going to the enclosed patches on the dikes where the sheep graze, the relationship between the sheep and cow parsley became clear. The sheep love to eat the flowers and leaves of the plant. The stem, however, remains untouched. As a result, the plant slowly withers away. Can this be a cue for humans to interfere with the landscape? Can I, as a designer, take the cowparsely out of the ecosystem to crerate something with it?

FIELDNOTES

And all of a sudden, the ferocity was shown. A cow parsley, still, exposed, and completely naked. It struck me and reminded me of a forest, burned and incinerated. As if the plant was at its final rest. Could the sheep have ever known? While I was standing there, I questioned one thing. Will this relic remain? Will it remain until the remnants are taken down by a biological process? Or, will it stay until the dikes are mown, the offcuts collected, and composted at a human address? Far from where it was grown. A cow parsley, still, exposed, and completely naked. Is this going to be your final dress? Maybe I can give you a second life? I can promise you I will bring you back.

And all of a sudden, the ferocity was shown. A cow parsley, still, exposed, and completely naked. It struck me and reminded me of a forest, burned and incinerated. As if the plant was at its final rest. Could the sheep have ever known? While I was standing there, I questioned one thing. Will this relic remain? Will it remain until the remnants are taken down by a biological process? Or, will it stay until the dikes are mown, the offcuts collected, and composted at a human address? Far from where it was grown. A cow parsley, still, exposed, and completely naked. Is this going to be your final dress? Maybe I can give you a second life? I can promise you I will bring you back.

Noticing Through Fragility

Designers frequently approach design from a material-driven perspective. As designers and makers, we can become deeply entangled in the pursuit of a meaningful outcome. However, the complex assembly of artifacts, materials, skills, tools, and opportunities makes the outcome of a material-driven design process unpredictable and unsure. Traditionally, designers tend to continue their process until the outcome meets their expectations. During this process, many materials are considered unsuccessful or failed, and are often rejected without much contemplation. However, most of the time, these failed experiments still hold value and can inspire the project toward unexpected and possibly meaningful directions. The design process was steered away from designer biases, prioritizing the exploration of fragile and precarious moments. These moments were considered as valuable cues originating from non-humans within the design process.

Designers frequently approach design from a material-driven perspective. As designers and makers, we can become deeply entangled in the pursuit of a meaningful outcome. However, the complex assembly of artifacts, materials, skills, tools, and opportunities makes the outcome of a material-driven design process unpredictable and unsure. Traditionally, designers tend to continue their process until the outcome meets their expectations. During this process, many materials are considered unsuccessful or failed, and are often rejected without much contemplation. However, most of the time, these failed experiments still hold value and can inspire the project toward unexpected and possibly meaningful directions. The design process was steered away from designer biases, prioritizing the exploration of fragile and precarious moments. These moments were considered as valuable cues originating from non-humans within the design process.

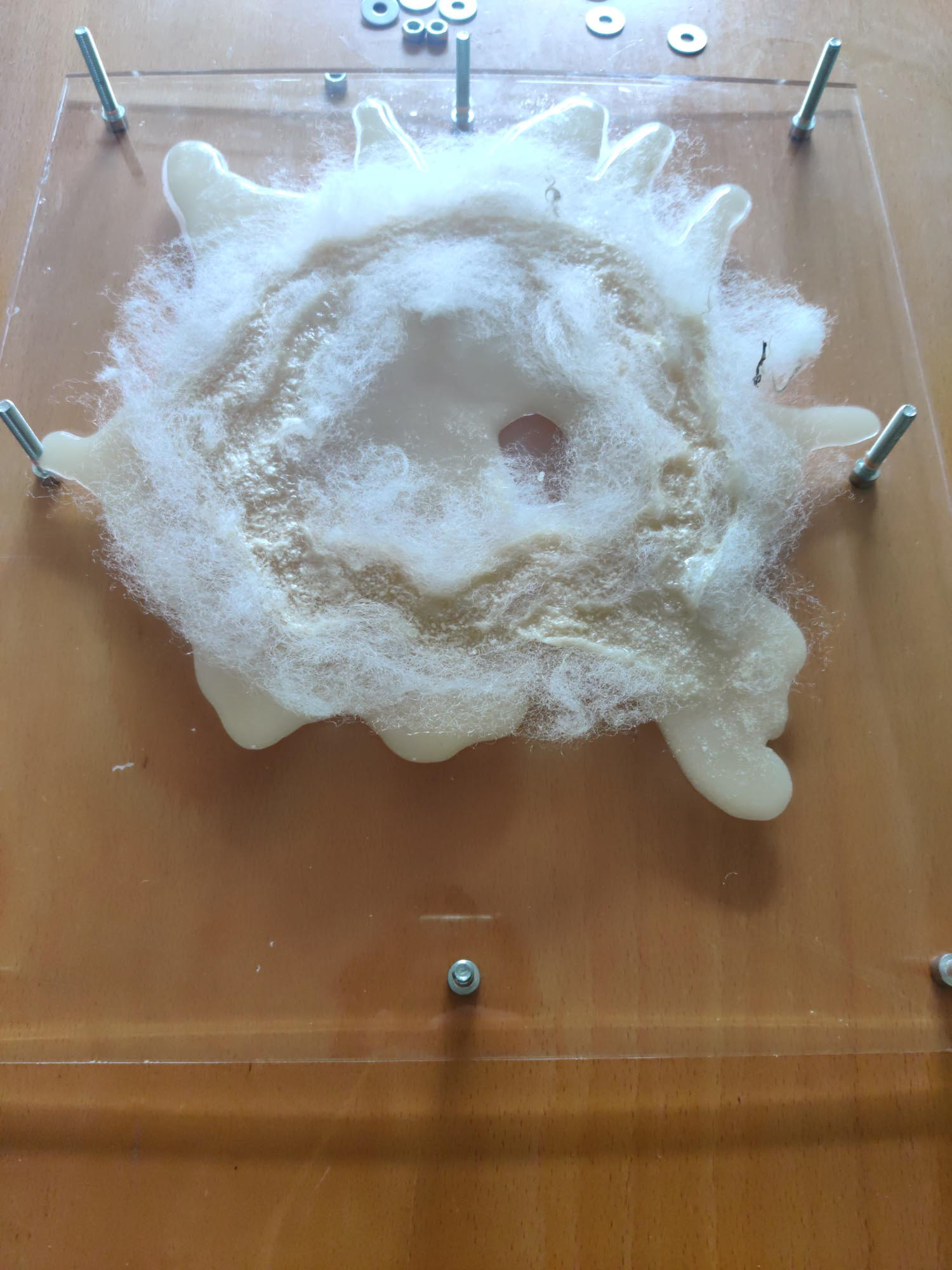

One of the earlier samples I was excited about was the white circle sample (see figure above). I made the sample by preparing an agar bioplastic with glycerine, water, agar agar, chalk, and tufts of wool. I then mixed all the ingredients in a pan and heated the mixture to approximately 95C. After this step, I took a glass oven dish and smeared the bioplastic-wool mixture onto the dish. Next, I used a different oven dish to flatten the bioplastic into a thin sheet. The sample came out nicely and for the first time during the project, I had the feeling I might have created something interesting. I was so excited about the material sample, that I cut the material sample in a circle, just so that it would look even better. The material was strong and sturdy, and it gave the idea of a felted sheet of wool, even though it was not felted. In addition to that, the material felt soft. It almost felt like suede. Yet, there was one ’problem’. The wool was not evenly distributed over the material sample. because of this, the material had clumps of wool, making the material thicker on some parts. One of these thicker clumps of wool had appeared on the edge of the material sample, and, after cutting the material sample in a circle shape, that clump started to fray. It felt like a problem I could not overcome. I tried evenly smearing the mixture onto the glass dish. Yet, this was extremely difficult to do as the clumps of wool had already formed in the pan. I also tried laying out the wool in the glass dish before pouring the bioplastic mixture over the wool. Although this resulted in a more evenly dispersed sample, the bottom of the sample now had more wool than the top layer.

Throughout the project, I learned that defining a sample as 'failed' or labelling elements as problematic is viewing the material process from a predominantly human-centred perspective. From a more-than-human perspective, these failed and problematic elements are merely occurrences that could, and perhaps, should be explored further. Concerning the sample shown above, the fraying of the wool was further explored by trying to recreate the fraying, resulting in multiple different samples.